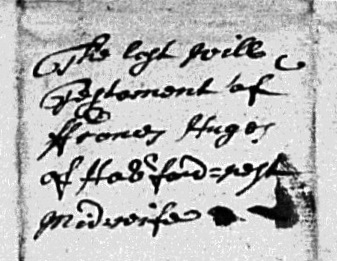

The Last Will and Testament of Frances Hughes of Haverfordwest, Midwife

National Library of Wales SD/1700/56

Frances Hughes was a midwife and widow who died in Haverfordwest in 1700. The only clues we have of her existence are found in her will, which was drafted on 26 April of that year. She died just a few days later.

We know nothing of her age at the time of her death, the details of her former occupation or that of her late husband (or husbands), but her will does provide some fascinating evidence about her circumstances at the time of her death, and offers a few tantalising clues about what appears to have been a long and perhaps eventful life.

At the time of her death she lived in a five room house consisting of two bed chambers, a garret, a small parlour and a kitchen. This in itself suggests she must have had some degree of wealth during her life as this was a substantial size house for the time, even in a market town such as Haverfordwest. Throughout Wales in the early modern period most homes were small and sparsely furnished, with single-room dwellings and small cottages being common. Frances, or at least her late husband, was likely one of the more well-off members of the town.

Despite the size of her home the moveable possessions recorded in her probate inventory were valued at the modest sum of £12. To put this in perspective, a study of fifty-six spinster wills from the Diocese of St David’s between 1700 and 1715 revealed a range of inventory values from as little as 2d to as much as £322, with many under £20, and eighteen with £10 or less.* A large portion of these women were rural householders able to maintain themselves through subsistence farming, however most lived in much smaller houses. It would appear that Frances had a substantial house with a modest but comfortable level of wealth. She was essentially house rich but cash poor(ish) in an early modern sense.

At the time of her death Frances was likely quite old, which is made brutally evident by the repeated and somewhat bleak use of the adjective ‘old’ before virtually every item in the probate inventory drawn up following her death. Her inventory consisted primarily of domestic goods, including three bedsteads, featherbeds, tables, chairs, a chest of drawers, a rug, linens, clothing and a parcel of old wool, as well as kitchen goods such as pewter dishes and plates, brass pots and pans, a cauldron, spits and a dripping pan, billows and skillet.

She’s was far from wealthy when she died, but it doesn’t appear as though she was suffering in abject poverty either. That she possessed a range of household goods suggests she was living in her own home and was able to support herself at the time of her death, although the pattern of bequests in her will does suggest one of her children may have been caring for her.

In her will Frances listed six surviving children from at least two different marriages, all of whom had different levels of independence. She left one shilling to a son named John Roberts, who was a millwright; ‘seventeen or eighteen shillings’ to her son Joseph Gwillum, a farmer, to buy a ring; forty shillings to her son Thomas Gwillum, who had no occupation given; one shilling and some clothes to her daughter Sibley Davies of Sutton; one shilling to her son Richard Gwillum, a smith. The rest of her estate and clothing was left her daughter Ann Bowen and granddaughter Mary Bowen. Ann was also made executrix of the will.

This discrepancy in bequest is not necessarily indicative of favouritism, but is likely a reflection of her children’s own level of independence. John Roberts and Richard Gwillum, the two children who were left the least, were both in occupations in which they could conceivably sustain themselves more readily. Given their professions of millwright and smith they were probably in better financial positions than her other children. Likewise her son Joseph Gwillum, who was a farmer, was bequeathed less than his brother Thomas, who appears to have had no notable occupation, and therefore may have been in worse financial circumstances. Her daughter Sibley was likely married and living in a more stable, sustainable circumstances resulting in her smaller bequest as well.

This leaves Ann Bowen and her daughter Mary Bowen who inherited the majority of Frances’s possessions. Although we can’t know for certain it is possible that Ann and Mary were living with Frances in a reciprocal relationship with Ann providing care for ageing her mother and Frances providing a home for her daughter and granddaughter. It is quite possible that Ann was herself a widow who would have been in a much more precarious financial situation than her siblings, thus warranting her receipt of the lion’s share of her mother’s possessions. Furthermore, that Frances appointed Ann to be her executrix suggests that Ann had a clearer understanding of her mother’s wishes, which would be the case were they living in the same house.

Another interesting clue about Frances’s life comes from the differences in surnames of her sons. These suggest she had been married and widowed at least twice if not three times. John Roberts was probably her eldest surviving child from her first marriage, with the remaining three Gwillum sons from her second. But Frances herself was neither a Roberts nor a Gwillum at the time of her death – she was a Hughes. The husband who predeceased her was not mentioned in her will, but it is possible that she had been married and widowed a third time.

And what of her own profession of midwife? Unfortunately there is very little we can glean about that from this document. We only know she was a midwife because the appraisers listed her as such. We know very little about the practice of midwifery in early modern Wales in general, although documents such as applications for licenses to practice midwifery do exists, but have yet to be studied in detail. Much more is known about midwifery in England during this time.

What is apparent is that Frances Hughes had at least some level of modest prosperity during her life, and given her dwelling at the time of her death her last husband had a degree of wealth and standing. That her appraisers saw fit to list her own profession suggests it held some significance, and as such she was likely a respected member of the community. At present this document stands very much in isolation and cannot be seen as evidence of a norm, but in these regards it would appear that Frances Hughes did fit the mould of an early modern British midwife. It is also clear that much more research is needed.

——

*This post is very much indebted to Lesley Davidson and her chapter ‘Spinsters were Doing it for Themselves: Independence and the Single Woman in Early Eighteenth-Century Rural Wales’ in Michael Roberts and Simone Clarke, eds., Women and Gender in Early Modern Wales (Cardiff : University of Wales Press, 2000), pp. 186-209.