In Breast Cancer in the Eighteenth Century (which I recently reviewed) Marjo Kaartinen notes that this disease was a great equaliser which afflicted rich and poor women alike. First-hand accounts of the experience of breast cancer are rare, and those that do exist are typically from more well-off women. Rarer still are reports which discuss the diagnosis and treatment of women from the lower ranks of early modern society, however I was fortunate enough uncover a brief but revealing case on a recent research trip to Powys Archives.

Prior to poor law reforms in the nineteenth century those who were not able to provide for themselves could appeal to their parish of legal settlement for support. This support was in cash or kind and provided the basic necessities of life including food, clothing and shelter as well as medical care. As such records kept by parish overseers of the poor can provide evidence of diseases and their treatments.

The case which I discovered is tragically and frustratingly short, accounting only for what the parish spent on one woman’s care, but it does provide a glimpse into life of someone who likely suffered and ultimately died from the disease.

In 1792 the overseers of the poor in the parish of Meifod, Montgomeryshire (now in modern-day Powys) made seven separate payments relating to the care of one Elizabeth Humphreys, a poor widow who was likely under the age of 45 and who most probably had breast cancer.

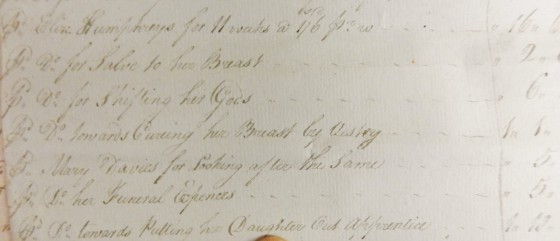

Record of parish support of Elizabeth Humphreys

Reproduced with permission from Powys County Archives (M/EP/41/O/RT/3 unsorted)

Either through the course of her illness or her financial circumstances or both Elizabeth was no longer able to financially support herself. From this record we know she suffered for at least 11 weeks before succumbing to her illness as this was the duration of the support provided, but she was likely ill for some time before this. This payment of 16 shillings and 6 pence was paid directly to Elizabeth, which indicates that she was still physically able to care for herself, as at this point there is no mention of another parishioner being paid to care for her. What her circumstances were prior to her receipt of parish support, and just how sick she was we don’t know, however she does not appear to have been in receipt of parish support prior to this.

Over the course of her illness Elizabeth was provided with at least two medical treatments, one of which was a salve, which could have been the popular ‘goose dung and celandine’ treatment discussed by Kaartinen (p. 59), or something more aggressive and caustic such as mercury, hemlock or carbonic acid (pp. 32-34). The second treatment is described only as a cure by vestry, which suggests parish officials acquired the services of a professional medical practitioner who may have even operated on Elizabeth, as lumpectomies and mastectomies were seen as options in all but the most advanced of cases.

Following this treatment Elizabeth was cared for by a Mary Davies, which suggests that she could have been further incapacitated by an invasive procedure.

Prior to this treatment an expense was incurred for the movement of Elizabeth’s goods. This could have been part of the preparations made in advance of an invasive surgical procedure which would have necessitate a lengthy recovery period in the home of Mary Davies, or it was because it was clear that her illness was terminal and the parish was making arrangements for the provision of palliative care.

Whatever the treatment was we know it was not successful, as the following entry is for funeral expenses for Elizabeth, and she was either buried in January or June 1792 (the burial register lists two Elizabeth Humphreys in that year, both of whom were widows and both were paupers). Sadly, Elizabeth left behind a young daughter who was likely under the age of 12 as she was subsequently placed in an apprenticeship, which gives us a clue to Elizabeth’s age range. As an apprentice Elizabeth’s daughter would have learned practical skills in housewifery rather than one of the trades associated with professional apprentices, and the apprenticeship would have served as a foster home for the orphaned girl. Unfortunately her indenture does not appear to have survived.

Although at presentit is not possible to know any more about Elizabeth Humphreys and her illness, it is clear that when individuals were inflicted by diseases such as cancer but were not able to support themselves certain measures were in place to ensure that they did receive whatever care was reasonably available and within the means of the parish.

(with thanks to Kerry and Roz at Powys County Archives)

Further Reading

Lorie Charlesworth, Welfare’s Forgotten Past (London: Routledge, 2010)

David W. Howell, The Rural Poor in Eighteenth-Century Wales (Cardiff: Cardiff University Press, 2000)

Marjo Kaartinen, Breast Cancer in the Eighteenth-Century (London: Pickering Chatto, 2013)